Are the UK's Trade Deals Reflecting Consumer Priorities?

The UK has been negotiating a wide range of new trade deals as part of its trade policy since leaving the EU. Many of these deals have been continuity agreements, but starting with the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with Japan, the UK is on course to negotiate and sign a wide range of new trade agreements.

While a large focus of trade talks will be the export and investment opportunities for UK businesses, the trade deals that the UK agrees have much wider impacts on people’s everyday lives - the choices they make, the prices they pay, the standards they can expect and the rights they can rely on.

In 2020, Which? hosted the National Trade Conversation (NTC) – a series of public dialogues around the UK, with people from a wide range of backgrounds, to understand what they thought should be the Government’s priorities for consumers when negotiating new trade deals. This autumn we reconvened participants from these dialogues, one year on from their last deliberation, to reconsider the issues and assess the Government’s approach to negotiations. We also conducted a nationwide survey, representative of the entire population, as well as specific nations.

Four priorities consistently emerged from our initial dialogues and were strongly reinforced in our most recent research:

- Maintain health and safety standards for food and products.

- Protect the environment.

- Maintain data protection regulations that protect consumer rights.

- Help address regional inequalities by protecting and promoting jobs, skills and industries across the UK.

This paper assesses the extent to which the UK Government’s approach to trade policy and trade deals is in line with public expectations, and identifies the priorities for the next stage of negotiations in order to ensure consumer interests are addressed.

pdf (340 KB)

There is a file available for download. (pdf — 340 KB). This file is available for download at .

Executive summary

The UK has been negotiating a wide range of new trade deals as part of its trade policy since leaving the EU. The first major deal to be agreed as part of a new independent UK trade policy was the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with Japan, and an agreement in principle (AIP) has been reached with both Australia and New Zealand. But whether accession to the 11 Pacific-rim member Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is next or initial trade talks with India proceed further, the content of all negotiations have important implications for consumers – the choices they make, the prices they pay, the standards they can expect and the rights they can rely on.

In 2020 Which? hosted the National Trade Conversation (NTC) – a series of public dialogues around the UK, with people from a wide range of backgrounds, to understand what they think should be the government’s priorities for consumers when negotiating new trade deals. This autumn we reconvened participants from these dialogues, one year on from their last deliberation, to reconsider the issues and assess the Government’s approach to negotiations. We also conducted a nationwide survey, representative of the entire population, as well as specific nations. Four priorities consistently emerged from the initial research conducted in 2020 – and were particularly strongly reinforced in our most recent research:

- Maintain health and safety standards for food and products.

- Protect the environment.

- Maintain data protection regulations that protect consumer rights.

- Help address regional inequalities by protecting and promoting jobs, skills and industries across the UK.

Which? explored these issues in detail in our research, sharing the texts of recently agreed deals and ongoing negotiations. We also assessed the extent to which the Government’s approach was in line with consumers’ expectations and what its priorities now needed to be to ensure that they are met.

Overall, we found that there was still a high level of engagement with trade issues among the participants from our dialogues. But, in contrast, our survey found a low level of awareness of trade deals across the population, and scepticism that consumer interests would be taken sufficiently into account as part of negotiations. The majority of people (67%) felt that the Government currently provides ‘too little’ information to consumers about new trade deals that it is negotiating. There was enthusiasm for the government increasing the amount of information online and for any communications to have consumers in mind, both in terms of the language used and the presentation of facts.

Reflecting consumer interests

Our research findings demonstrate that there is a clear appetite for consumer views and the impact on consumers needs to be taken fully into account as the UK Government negotiates trade deals – and support for a specific consumer chapter to be included within each trade deal.

The agreement in principle with New Zealand has set an important precedent for this with the inclusion of a consumer protection chapter – a world first.

‘In terms of taking account of the views of people, the UK government needs to consult with people from everyday life and representatives of various sectors before signing trade deals. Too much happens behind closed doors and without consultation. The government could learn from this research which is being undertaken by Which?.’

- Male, 45–54, Northern Ireland

- A consumer chapter that reinforces consumer interests throughout other chapters, needs to be an objective for all trade deal negotiations.

Standards for food and products

Maintaining food and other consumer product standards was a priority in our original NTC – and the reconvened participants described it as being of equal or increased importance. For some, the Covid-19 pandemic had increased its importance. For others, the effect trade deals can have on food standards has been highlighted by trade discussions that have occurred over the past 12 months. 91% of survey respondents agreed that the UK Government should make sure that when agreeing trade deals, the same food safety standards should apply to food imported from other countries as well as food produced in the UK. 87% also agreed with this for animal welfare, and 84% for environmental protection. People in both our survey and our reconvened dialogues rejected the idea of differentiating the tariffs that are applied to imports based on whether products meet UK standards or not. They expected all imported food to meet UK standards.

‘I think maintaining the food standards and welfare is the most important as we have very high standards in the UK and would not want to compromise when doing any trade deals with other countries. We have built up a good reputation in this country in regards to animal welfare and the quality of food and would not want to jeopardise that.’

- Female, 55–64, Northern England

The UK Government has made clear commitments that it will not compromise on standards and has explicitly stated that it will not compromise the ban on use of beef hormones in order to reach a deal with Australia, for example. But it’s still too early to see the extent to which this will be delivered through ongoing trade talks. While text in trade deals does not force or ban changes to our standards, free trade agreement (FTA) partners may have expectations of subsequent changes because of the text the UK commits to. It is for example unclear what provisions allowing for recognition of ‘equivalence’ of standards will ultimately mean for the protections consumers can expect. A new Trade and Agriculture Commission (TAC) has been appointed to assess the implications of trade deals for environmental and welfare standards, but it does not have consumer interest expertise among its membership.

The Government must demonstrate through the ongoing negotiations that it will stick strongly to its commitments not to compromise on UK standards and consumer protections.

- The Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Food Standards Scotland (FSS) need to play a more central role in ensuring that consumer interests are taken into account and upheld in relation to food standards – including where standards and the level of protection consumers expect may relate to factors that go beyond a scientific risk assessment, such as ethical issues.

- The Trade and Agriculture Commission, given its important role assessing trade deals against UK standards, must have stronger consumer interest representation.

- The Government should also support the recommendations within Henry Dimbleby’s National Food Strategy proposals and set out the core environmental and animal welfare standards that underpin its approach to trade negotiations, which it needs to commit to uphold, alongside food safety. There also needs to be a mechanism for how these will be applied. Our consumer research shows clearly that the vast majority of consumers do not support the use of a dual tariff approach and want standards applied to all imports.

- The Government needs to ensure that any provisions relating to recognition of equivalence of standards or conformity assessment – either directly within trade deals or through subsequent mechanisms that they establish – will not weaken UK standards for imported food and consumer products or prevent future raising of regulatory levels.

Environmental protection

One of the most striking findings from the latest Which? consumer research was the proportion of people who felt that maintaining environmental protection was even more of a priority compared to their view last year. With the number of extreme weather events over the past 12 months increasing, many feel urgent action is needed to protect the environment. Considering the impact on the environment of international trade is therefore viewed as a moral responsibility, especially when trading with partners a significant distance away from the UK.

‘I think it’s very important to protect the environment, more than I did last year for sure. This year we’ve witnessed many global catastrophes as a result of climate change, and the shocking scenes seen on our screens has really made me more conscious than ever as to what’s happening.’

- Female, 55–64, South Wales

Co-operation on environmental protection, including tackling climate change, has been a commitment within the recently agreed trade deal with Japan and the agreements in principle with Australia and New Zealand. The desire for precedent setting provisions is an agreed aspiration for the New Zealand FTA. But it is as yet unclear what these will involve. In its net zero strategy published ahead of COP26, the UK Government also stressed that: ‘Decisions on the liberalisation of partners’ goods must account for their environmental and climate impact. Where there is evidence that liberalisation could lead to significant carbon leakage, the case for maintaining tariffs or pursuing conditional market access, through clauses on standards or eco/carbon intensity, should be carefully considered.’

The UK Government must build on its leadership role at COP26 and be a global leader in promoting trade that supports its climate and wider ambitions:

- Environmental protection and tackling climate change must be a central pillar of all new trade deals, and the deals that the Government signs must support the UK’s transition and not undermine it.

- The Government must conduct a full environmental impact assessment to understand the implications of any trade deals on its net zero commitments, as well as other environmental impacts before deals are finalised.

- All chapters across a trade deal must be carefully assessed from an environmental protection perspective in order to ensure that they will support the UK’s ability to meet its net zero ambitions. This includes, for example, ensuring that climate friendly regulations will not be obstructed and linking tariff reductions to environmental commitments. They should also not result in trade flows that will undermine or undercut national initiatives to drive sustainability goals.

- The Government should report annually on progress that has been made through cooperation provisions within its FTAs.

Data protection and digital rights

Another key consumer priority identified by our NTC participants was ‘Maintain data protection regulations that protect consumer rights’. Participants could see the economic opportunities of digital trade. However, there were also widely held concerns about what the implications of elements in trade deals intended to facilitate freer flows of data, that enable smoother digital trade, might be for the protection of consumer data and online rights.

This feeling has also intensified as a result of the pandemic, which had resulted in many participants leading much more of their lives online. Many participants also felt the rate of online scams had increased since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. More widely, participants cited data breach scandals and media coverage of data misuse as contributing factors in the increased importance of the UK Government not trading away existing data or digital rights protection in future agreements.

‘Digital protections have been a higher priority in my eyes due to the huge rise of online fraud and scams during the pandemic.’

- Male, 45–54, South Wales

Despite the Government’s attempts at reassuring consumers that it’s committed to maintaining high standards of data protection, including when it is transferred across borders, the wording in the UK-Japan CEPA establishes a worrying precedent. Provisions in the CEPA promote compatibility between data protection frameworks of different standards. It recognises international guidelines and voluntary undertakings as equally as sufficient methods of data protection as a stringent data protection framework. Both of these are less comprehensive than the protections the UK’s current data protection framework offers, which is underpinned by the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR). The UK’s data protection framework is internationally recognised as being of a high standard and the UK is currently consulting on proposals to make changes to it.

The UK-Japan deal also bans mandatory disclosure of source code, software and algorithms in the software that they use, which includes algorithms used to target their products to consumers. This can pose problems in terms of accountability by limiting access to key information that may be required by regulators to tackle online harms and protect consumers.

In order to deliver on the expectations of consumers, the UK Government must:

- Ensure that provisions relating to digital trade and data flows within trade deals being negotiated uphold the protections that consumers can expect under the current UK GDPR regime.

- Promote consumer rights in digital trade and enhance regulatory co-operation on cross-border trade with its trading partners. Opportunities such as agreeing roaming provisions to benefit tourists and business travellers should also be pursued.

- Explain how its ability to enhance legislation on online harms, in line with the wider government agenda to place greater responsibilities on online platforms for the safety and accuracy of their content, is not undermined by Treaty commitments made within new trade deals.

Regional equity

The final priority participants discussed was for trade deals to ‘help address regional inequalities by protecting and promoting jobs, skills and industries across the UK’. While not solely a consumer concern, many of the participants in the NTC felt strongly that trade deals should bring benefits to the whole of the UK, not just London and the South East. Some also felt it was important to ensure there was help for those who needed to reskill if their industry lost out due to changing trade patterns. When we asked the participants in this year’s research how important this priority was in 2021, many thought it was of increased importance to achieve this priority given the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the UK.

‘I don’t remember feeling too strongly about it last year, but I think it is now more important as certain regions have been more badly impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic than others have.’

- Male, 25–34, Southern England

From considering the impact assessment of the Japan deal and participants’ responses, it is evident that a lot more could be done to detail and convey what consideration is being given to regional equity and the expected impact of trade deals once they are signed.

The Government should ensure trade deals can provide meaningful opportunities and benefits for people and businesses across the country:

- Advisory bodies set up to inform the government’s approach to trade deals need to be drawn from across the UK, but also from different interest groups, including consumer representatives. The Strategic Trade Advisory Group (STAG) has representation from a broad range of interests, but it is important that wider advisory groups ensure representation and insight from across the UK.

- The Government should undertake its own trade dialogues with people from across the UK to inform policy, ensure views particular to nations and regions are identified and understood, and improve wider engagement with the public. As Which? has demonstrated, such research delivers informative insights and also heightens public understanding of the complex topic of trade. This would also provide further aspects for assessing the impact of new agreements on the nations and regions of the UK.

Transparency and scrutiny

There were strong demands for the government to be more transparent about the trade deals that it is negotiating in our research. Just 6% of people, for example, knew that the UK had signed a trade deal with Japan. This requires much more effective consumer engagement as set out above. People also had strong expectations that there was more effective Parliamentary scrutiny than is currently required.

‘A lot of the info around trade deals is confusing but the general public need to be aware of the decisions the Government is faced with and what they propose to do.’

- Female, 35–44, Southern England

- The Government should build on research from Which? and ensure that there is greater transparency and more effective public engagement around ongoing trade negotiations. This includes effective Parliamentary involvement and scrutiny.

- The Government should look to best practice from other countries and create more meaningful and accessible websites covering each trade deal and enabling people to easily understand what negotiations are aiming to achieve and how they are progressing.

Introduction

The UK has been negotiating a wide range of new trade deals as part of its trade policy since leaving the EU. Many of these deals have been continuity agreements, but starting with the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with Japan [1], the UK is on course to negotiate and sign a wide range of new trade agreements which could have a significant impact on consumers, the choices they can make, prices they pay and protections they can expect. Trade deals are international treaties making binding commitments which cannot easily be changed.

Agreements in principle (AIP) have now been reached with Australia [2] and New Zealand [3]. These contain agreements on the main issues that will be included in the deals, but which have still to be translated into formal text and therefore international law. The UK is seeking to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) which includes 11 Pacific-rim countries as members. The UK Government has also been in pre-negotiation talks with India, the Gulf Cooperation Council and consulted on updating deals with Mexico and Canada. Negotiations are additionally under way with Singapore on a Digital Economy Agreement. While the USA is still a UK priority, trade talks have been put on hold under the Biden Administration.

While a large focus of trade talks will be the export and investment opportunities for UK businesses, the trade deals that the UK agrees have much wider impacts on people’s everyday lives. To understand what matters most to people about trade deals when they have a detailed understanding of the issues that could be part of the negotiations – including greater access to a range of goods and services – Which? held the National Trade Conversation (NTC) in 2020 [4].

The Conversation took place in Northern England, the East Coast of Scotland, Northern Ireland, South Wales and Southern England. Over five virtual workshops people learned about what the UK trades, how trade deals are negotiated and what the key issues are for the Government’s priority trade deals. After much debate and questioning, four issues emerged as the overall priorities for most of the people who took part.

- Maintain health and safety standards for food and products.

- Maintain data protection regulations that protect consumers rights.

- Protect the environment.

- Help address regional inequalities by protecting and promoting jobs, skills and industries across the UK.

This research focussed solely on non-EU trade due to the unique situation of the UK-EU trade negotiations compared to those of the other trade negotiations the UK has and will look to undertake.

One year on from our NTC and with the UK’s approach to trade policy now more advanced, Which? reconvened participants from the NTC to understand their views on the government’s approach since the first Conversation and to see if their priorities had shifted.

National Trade Conversation: Reconvened

Which? reconvened participants from the National Trade Conversation (NTC) to understand their views on the UK Government’s approach since the first Conversation and to see if their priorities had shifted.

In total, 37 participants from the original research group took part in an online community, running from 13–18 September 2021. In the community, participants revisited each of the four consumer priorities identified in the NTC and discussed the importance of each a year on. They also assessed the Government’s achievements in each area. A summary of what evidence participants engaged with is included in the annex of this report.

The participants selected to take part were from a range of backgrounds. The demographic mix of the group was broadly in line with the general population in terms of gender, age, ethnicity and disability. Which? also recruited participants who voted in line with the results of the 2016 EU referendum, and made sure that each of the five original NTC locations from across the four UK nations were represented in the group.

Which? also supplemented this deliberative research with a survey [5] that was representative of the UK population to find out people’s views on how trade negotiations were progressing and what they considered to be most important.

This paper draws on the findings from our latest Which? consumer research, assesses the extent to which the UK Government’s approach to trade policy and trade deals is in line with public expectations, and identifies the priorities for the next stage of negotiations.

Consumer expectations and priorities

Awareness of UK trade negotiations

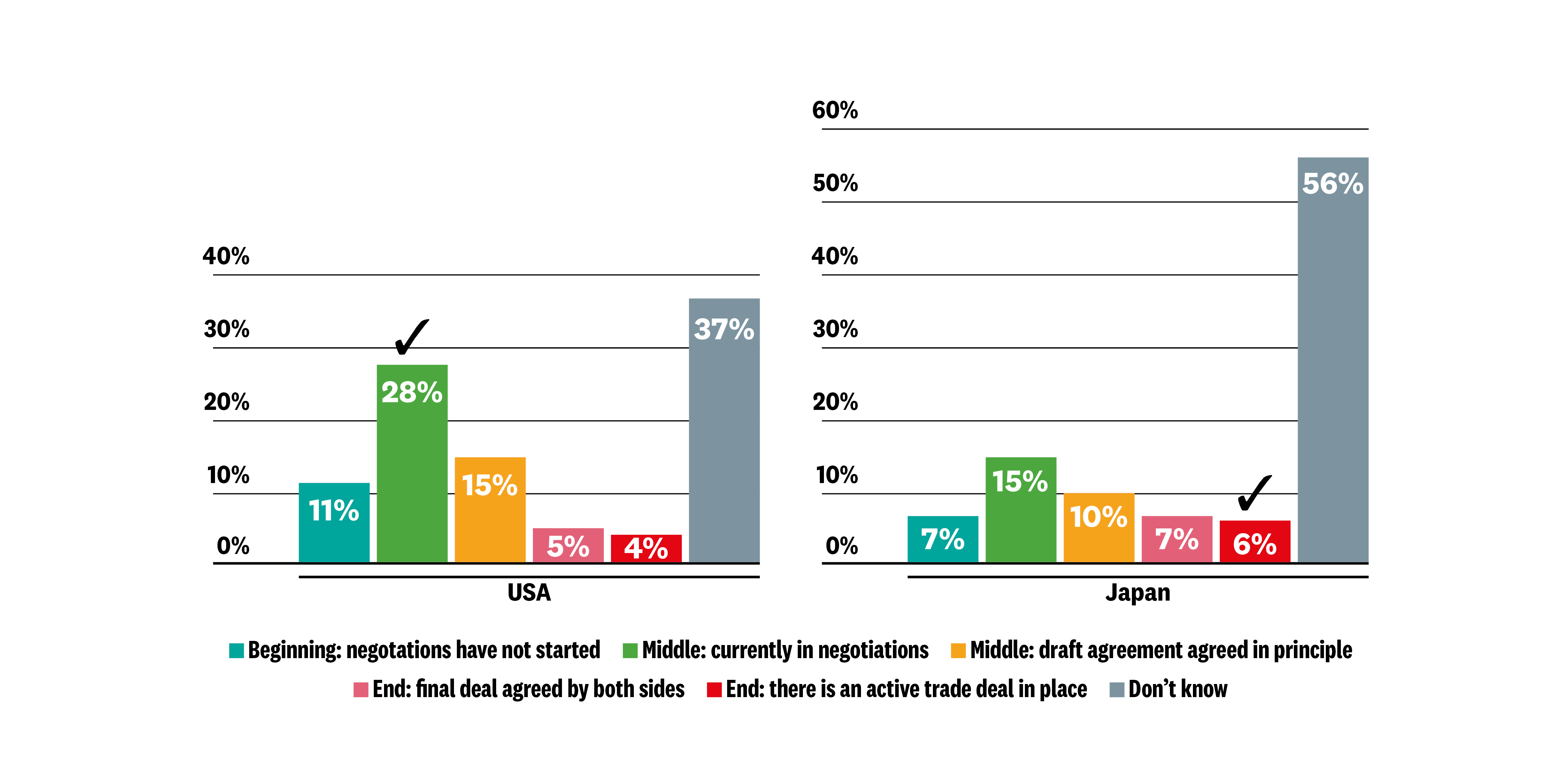

In June 2021, Which? conducted research with a nationally representative group of 3,263 consumers to understand their views and attitudes towards international trade. We found many consumers lacked knowledge of the current trading status between the UK and a variety of countries. For instance, only 6% correctly identified that the UK and Japan have an active trade deal in place, despite the UK-Japan CEPA being the first new deal the UK signed after leaving the EU.

Overall, a high proportion of respondents told us they simply didn’t know what stage of negotiations the UK is in. For instance, the fact that the USA and the UK were ‘currently in negotiations’ at the time of our survey was correctly identified by 28% of respondents, which was the highest proportion to select the right answer across the eight countries we asked about. However, a higher proportion (37%) said they didn’t know the status of UK-USA negotiations, and the remainder selected an incorrect stage of negotiations [6].

Knowledge of the status of UK trade deals in June 2021

It is important to note that these results are not due to a lack of interest, as there is clear demand from consumers for more engagement from the government. Trade talks can also move slowly. The majority of survey respondents (67%) felt that the UK Government currently provides ‘too little’ information about new trade deals it is negotiating, compared to 16% who said the amount of information they receive from the Government is ‘just right’.

Importance of representation

The research demonstrates a clear appetite for the consumer view and the impact on consumers to be more fully taken into account while the UK Government decides trade policy. 83% of respondents felt it was important that consumer groups are included when discussing UK trade policy; 47% said this was very important. Over half of consumers (57%) thought consumer groups would be invited to take part in expert discussions to provide input on the UK’s trade negotiations and trade strategy. Despite this, some of the Government’s trade advisory groups do not have consumer groups in their membership.

Consumers were less confident in their expectations of representation: 74% of survey respondents thought the interests of manufacturers would be represented to a great/some extent in trade negotiations, while 53% felt consumers would be similarly represented. There was even lower levels of optimism from consumers in the devolved nations – 54% of consumers in Northern Ireland said they were ‘not at all confident’ that trade deals the UK Government is making reflect the specific needs of Northern Ireland, with 41% and 32% on consumers not at all confident in Scotland and Wales respectively [7].

Consumer perceptions of how trade deals reflect the needs of the devolved nations

More informed expectations

The participants in our online community had a higher than average awareness and understanding of trade, given the 12 hours they had each spent learning and discussing trade in the NTC last year. The level of engagement we achieved through the deliberative project last year was long lasting: when Which? re-contacted the original 97 members of the public who took part in the NTC, more than 60 of them said they were interested in participating in another trade research project. This engagement was further highlighted by the responses participants gave in the community. We found evidence that many had retained a deeper and wider knowledge of trade, as well as an awareness of trade deals the UK had and were in the process of signing. Some participants spontaneously mentioned trade agreement developments with priority countries discussed in the NTC, as well as topics covered in the discussions last year.

‘The research into trade opened my eyes greatly last year, and made me consider things I had never thought twice about before. Trade now means to me how we get our goods and how easily and safely they get into my house.’

- Female, 18–24, Southern England

‘I’ve been keeping a lookout in the media to hear about any trade deals that have been finalised. I heard that a New Zealand deal was imminent.’

- Female, 45–54, South Wales

This level of awareness contrasts with the results of our survey in the previous section, which showed the average consumer is unaware of the status of many of the UK’s trade negotiations – and demonstrates the importance of more proactive engagement from the Government to increase the awareness and understanding of all consumers across the UK.

We asked participants in our online community how the government should further engage with consumers on trade negotiations and deals the UK is making. We suggested some potential ways, such as: a dedicated website, roadshows, press releases and targeted communications with a consumer perspective, and expanding the current regional trade and investment hubs to have a consumer facing role. Participants were generally very keen for the Government to do more to proactively communicate details of trade deals with consumers in a variety of ways. Participants were most enthusiastic about the Government increasing their online activity as this would be accessible and potentially wide reaching. Participants also wanted any communications to have consumers in mind, both in terms of the language used and the presentation of facts.

‘All of the above are extremely good ideas and I wouldn’t like to choose just one. I would like to see all of these happening to give as many people [as possible] the opportunity to gather information and put questions forward.’

- Male, 35–44, South Wales

Throughout the community, we provided participants with information about both the UK-Japan CEPA and the agreement in principle between Australia and the UK, giving them a sense of what the Government had committed to on behalf of consumers. Overall, participants were disappointed with the terms of the CEPA and felt the Government could have pushed harder to make sure the four consumer priorities identified as part of the NTC were more fully achieved. Many thought the Government had prioritised agreeing a final deal within a short time period and hoped future agreements would be more thoughtful. Participant responses to the four consumer priorities are explored in more detail later in this report.

As we found in our survey of consumers, participants in our community remained unconvinced that the consumer view is being adequately represented in trade negotiations.

‘In terms of taking account of the views of people, the UK government needs to consult with people from everyday life and representatives of various sectors before signing trade deals. Too much happens behind closed doors and without consultation. The government could learn from this research which is being undertaken by Which?’

- Male, 45–54, Northern Ireland

Regardless of their level of engagement, we found consumers wanted the government to do more on their behalf. This included both improving the information provision and communication channels it provided to consumers, as well as ensuring the consumer perspective was more evident in future negotiations. The inclusion of a consumer chapter in the UK-New Zealand agreement in principle is a positive step in this direction and should be built upon in future deals.

Progress on specific priorities

Food and product standards

One of the four consumer priorities identified in the NTC was to ‘Maintain health and safety standards for food and products’. It was a priority that many participants thought was very important for the Government to consider. There was pride in the UK’s current standards and confidence in the existing regime, and many thought the risks of reducing current standards outweighed the benefits. Some participants were concerned that changing standards could have a big impact on certain groups, such as those on a low income.

For all participants in our 2021 online community, this priority was either of equal or increased importance for the Government to prioritise compared to 2020. Aligning with our findings last year, participants felt any reduction in standards for food or consumer products was unwanted and unnecessary. For some, the Covid-19 pandemic has contributed to some participants’ views that this priority is of increased importance. For others, the effect trade deals can have on food standards has been highlighted by trade discussions that have occurred over the past 12 months, accentuating the importance of this priority.

‘In my opinion, the importance of standards has remained equally high to last year, although the public’s awareness of this area has increased dramatically. Trade deals with Australia and Japan have catapulted discussions over standards into the public eye, although for me the real test of the perceived importance of standards will be if/when the US and the UK come to devise a trade agreement.’

- Male, 18–24, South Wales

During our 2021 online community, we presented participants with some specific ideas of how food standards could be treated within trade deals. We asked participants to read an extract from the National Food Strategy independent review [8] which proposed the idea of ‘core standards’ that could be applied to food and agricultural imports. These ‘core standards’, as originally set out by the Trade and Agricultural Commission (TAC) [9], would be a set of standards that the UK Government commits to applying to imported food, including animal welfare and environmental and climate protections. Most participants were enthusiastic about the idea and what it could mean for the quality of food available in the UK if core standards were included as part of future trading negotiations.

‘I think it’s a really good idea as they are laying out exactly what they want and expect and that they are not prepared to compromise on animal welfare and standards in any way.’

- Female, 55–64, Northern England

However, a significant proportion of participants, while keen on the idea, doubted the likelihood of the UK Government actually endorsing core standards.

‘It’s all very well in theory, but I am sceptical about the practicalities of it. As I have [said] previously, we are already seeing a backtrack on climate and green credentials with the Australian deal.’

- Male, 55–64, South Wales

Our survey in June 2021 reiterates the consumer preference for a set of clear standards relating to specific elements of food production for both imported and domestically produced food. As shown in the graph below, 91% of survey respondents agreed that the Government should make sure that when agreeing trade deals, the same food safety standards should apply to food imported from other countries as well as food produced in the UK. 87% also agreed with the same sentiment when thinking about animal welfare, and 84% agreed when thinking about environmental protection [10].

Agreement that the same standards should apply for imported and domestically produced food

Participants in our 2021 online community were also asked about their views on an alternative idea, a ‘dual tariff’ regime which was proposed by the Government’s TAC. This regime would mean food that doesn’t meet UK import standards would still be allowed to enter the country, but would be subject to a higher tariff rate. The majority of participants did not like the idea of a dual tariff system and preferred for food that didn’t meet our current standards to not be allowed in at all.

‘I think food that doesn’t meet the standards should not be allowed in at all. I think this would mean less choice for consumers, but this is a price I am willing to pay.’

- Male, 25–34, Southern England

This finding aligns with the results of the Which? June 2021 survey, which set out three scenarios for consumers to choose between:

- Food produced to lower standards should be freely allowed into the UK.

- All food imported to the UK should continue to have to meet UK domestic food standards.

- Food produced to lower standards should be allowed into the UK but with a higher tariff/import tax.

The chart below illustrates the strong preference consumers have to retain the existing requirement for imported food to meet UK domestic food standards; very few (4%) wanted the dual tariff regime [11].

Consumer preference for standards of imported food

In our online community, participants reflected on some of the impacts a dual tariff regime could have. Some were confused as to how the regime would benefit consumers, making the assumption that the cost of the higher tariff would be passed on in the purchase price for consumers. A small proportion thought it could have a positive impact, providing an incentive to international suppliers to increase the quality of their food in order to avoid a higher tariff.

‘Generally, the public aren’t knowledgeable enough with regards to their food and may look at things from the point of if a product costs more, it must be more worthy, or a better quality rather than it not adhering to the UK’s standards, as the manufacturer couldn’t swallow these higher tariffs on a long-term basis.’

- Female, 25–34, Northern Ireland

‘If the tariff was that high on lower quality food then surely it would prove unprofitable to import, therefore making it an incentive to improve your product.’

- Female, 55–64, Northern England

It is clear from our research that consumers feel strongly that trade deals should protect the UK’s existing standards regime for food and consumer goods. At the end of the online community, participants were asked to rank the four priorities for trade deals that were identified last year in the NTC. ‘Maintain health and safety standards for food and products’ was most often picked as the highest priority, with 20 out of the 37 participants selecting this as the most important priority out of the four.

‘I think when we talk about trade the safety standards of the goods being traded is so fundamental that it has to be the primary consideration...lowering standards of food safety for import also forces domestic producers to lower their own standards in order to remain competitive – and this places UK consumers’ health at greater risk and lowers [the] quality of UK produce.’

- Male, 25–34, Southern England

Assessment of progress

The Government has made several public commitments to maintaining the UK’s high food standards, including in the Conservative Party’s 2019 manifesto. However, the Government did not agree to make this a firm legal commitment within the Agriculture or Trade Acts, as advocated for by Which? and other public interest groups.

Instead of a commitment to maintaining standards, which as our survey highlighted could include standards relating to safety and quality, environmental standards or welfare standards for example, the UK Government agreed to a provision within the Agriculture Act 2020 (Section 42) that before a trade deal can be agreed, the Secretary of State for International Trade has to provide a report to Parliament which explains whether, or to what extent, what has been agreed is consistent with the maintenance of UK levels of statutory protection in relation to human, animal or plant life or health, animal welfare, and the environment.

The Government also established an advisory commission, the TAC, to advise on how best the Government could advance the interests of British farmers, food producers and consumers in future trade agreements. Its focus was largely on environmental and animal welfare standards, so that it did not duplicate the remit of Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Food Standards Scotland (FSS). It reported in March 2021, making a series of recommendations, including the need for the Government to develop an agri-food trade strategy as part of a wider national food strategy. This would include ‘a process for preparing for, negotiating and conducting detailed assessments of trade deals, with a clear understanding of the implications, trade-offs and red lines that would be applied within them’ and ‘advancement of core standards, reflecting legitimate UK regulatory objectives on climate change, environment, animal welfare and ethical trade…’ It also emphasised the importance of the UK championing global standards and placed a strong emphasis on public engagement and transparency, as well as strengthening impact assessments of trade agreements.

More controversially, as set out above, it also proposed a dual tariff approach, proposing that the Government should take an ambitious approach to the liberalisation of the UK’s import tariff regime, for countries that can meet the high standards of food production expected from UK producers. ‘It should work with trading partners within future FTA negotiations to lower tariffs and quotas to zero where equivalence is demonstrated for these standards.’

The Government’s response to the TAC [12] reiterated many of previous general commitments to maintaining standards, without committing to some of the more specific proposals made by the TAC – including a strategy setting out how it would advance core standards and how the UK would work to develop stronger international standards.

Under the Trade Act, a new TAC with a new membership has also been put on a statutory footing in order to provide advice relating to the reporting requirement on standards under Section 42 of the Agriculture Act. It is therefore very disappointing that the membership of the TAC does not include any representatives with expertise on consumer interests.

The FSA and FSS will also have a role advising on trade deals. But unlike the TAC, the FSA and FSS do not have a formal assessment and reporting role in the same way under the Act. Their roles will, however, be critical in understanding what trade negotiations will mean for food safety, quality and wider consumer interests. It will therefore be important that they fully step up to their statutory consumer champion role and use their statutory powers to independently report on any implications for consumer protection before deals are signed.

Our National Trade Conversation also highlighted the importance people place on wider consumer product safety standards. Again, the Government has made general commitments to maintaining UK standards, but the detail that is agreed within particular trade deals, as well as any subsequent discussions on regulatory co-operation, will determine the extent to which the UK applies current standards to imports – and, crucially, recognises other countries’ standards as equivalent to our own.

Trade deals to date

The provisions relating to food within the CEPA with Japan largely repeat what had been agreed as part of the previous deal the UK was part of through membership of the EU. The Government highlighted some changes that had been made to how protected geographic status for certain foods would be applied (for example, Stilton cheese) and emphasised the opportunities there were for food exports to Japan. There were also some additional tariff reductions achieved on imports of Japanese products – such as udon noodles, Pacific bluefin tuna and Japanese beef. The Government has emphasised that CEPA maintains UK standards for food safety and animal welfare. The deal doesn’t make particular commitments to food standards. It has also created mechanisms for co-operation between Japan and the UK on sustainable agriculture and animal welfare but it is unclear whether these will deliver anything of substance.

Similarly, in terms of wider consumer product standards, provisions supporting co-operation in development of international standards and recognition of global standards in specific product categories, such as cars, were continued.

Australia and New Zealand

The trade deals with Australia and New Zealand will give a better reflection of the extent to which the UK Government will stand firm on food standards, given that agriculture is such an important part of both countries’ economies and a key aspect of the negotiations.

The agreements in principle with both countries give an indication of what has been agreed at a high level, but until the full texts are published, the full implications are not clear.

Both agreements will see a phased opening up of market access for Australian and New Zealand products, such as beef and lamb, with a phasing out of tariffs intended to allow UK producers to adjust. We know from Which? research that most consumers want to support UK farmers and have a choice of UK-produced food.

The chapters that will, however, be of most significance for how food and wider product safety standards are maintained are the chapters on sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures and technical barriers to trade (TBT). The former sets out what is permitted in relation to human, animal and plant health protections and the latter in relation to wider technical standards and regulations.

Australia

Positively, the Government has made it clear that the agreement with Australia will not in any way undermine the UK’s ban on beef hormones, which applies to imports. More generally, the countries have agreed that ‘imports will still have to meet the same respective UK and Australian food safety and biosecurity standards.’

The agreement in principle however does include the principle of equivalence of SPS measures where they achieve the other country’s appropriate level of protection and allows for the recognition of regional standards – and regional disease status in terms of controlling pests. How ‘equivalence’ of standards is assessed will be critical as it could allow Australian produce produced to lower standards (eg. in the case of pesticides where the UK has stricter controls) to be imported to the UK.

Henry Dimbleby, who has written the independent National Food Strategy review for the UK Government, has highlighted the differences in farming practices, including animal welfare standards and wider environmental impact. He has also stressed the risk that: ‘The way we do one trade deal inevitably feeds into how we do the next. Brazil – which has significantly worse environmental and welfare standards than our own, or indeed Australia’s – is also being lined up for a trade deal. If we are seen to lower our standards for the Australia deal, it will make it much harder to hold the line with Brazil – or the next potential trading partner, or the next.’

Dimbleby has also emphasised that there is a real risk that the Australia deal could undermine the Government’s focus on getting UK farmers to raise their environmental standards further – and that our true carbon footprint, including that from imports, would be larger than ever, as would the impact our food has on biodiversity. He therefore also recommended that, as well as maintaining the current standards that apply to imports, the Government develop a set of core standards that it can use for all future trade deals and explained how it would enforce them and thereby help to raise standards both here and abroad.

The Government has yet to respond to his recommendations. It will be publishing a White Paper on a national food strategy in the coming months – and so it is essential that this issue of core standards is addressed.

There is also intended to be a commitment to increase co-operation on technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment more generally – so also for wider consumer products, besides food – and to give positive consideration to the acceptance of technical regulations where they are found to be equivalent. There is a desire to cooperate on international standards and ongoing discussions on some specific products, such as cosmetics and medicines. As with food, any move towards greater alignment or recognition of others’ standards must ensure that there is no lowering of the protection UK consumers can expect – and ideally enhances it – but this is not guaranteed.

New Zealand

The AIP with New Zealand also recognises the principle of equivalence of SPS measures where the exporting country objectively demonstrates that its measures achieve the importing country’s appropriate level of protection. As with Australia, there is a focus on taking into account regional conditions, including what is permitted for pest control. There is also a standard provision in trade deals allowing for New Zealand and the UK to adopt emergency measures to address urgent problems of human or plant health protection. Going further, there is additionally a commitment to remove approval processes for establishments and facilities within the scope of the chapter (which would include meat and dairy plants, for example) and that food defined as ‘low risk’ does not require health certification under each other’s respective laws and regulations.

There is also a commitment to enhance co-operation on antimicrobial resistance and the use of antibiotics in animal rearing, both bilaterally and in relevant international fora. There is a specific chapter on co-operation on animal welfare and within this ‘recognition that New Zealand and the UK’s farming practices are substantively different, but each country accords a high priority to animal welfare in those practices, and that in multiple areas their respective animal welfare standards and associated official control systems provide comparable outcomes.’ It is therefore crucial that these ‘outcomes’ do not lead to any weakening of the standards that consumers expect at all stages of production.

On wider standards and technical regulations relating to consumer products, there are commitments to cooperate, including a focus on conformity assessment and accreditation, as well as on market surveillance. As with Australia, specific provisions relating to certain products, including cosmetics and medicines, will be set out. How equivalence of standards will be assessed in practice, taking into account on the ground realities, will again be essential. It is however difficult to fully evaluate these provisions until the final text is available.

Other trade deals

The UK has also formally begun the process of accession to the CPTPP. This is a strategically important deal for the UK, but also means that as the UK is trying to join a deal that has already been agreed, there is limited scope to deviate from the existing text. Australia, New Zealand and Japan are all parties to the agreement, as are other countries where the UK wants more ambitious bilateral agreements, such as Mexico and Canada.

Many of the countries that are party to the agreement have different approaches to regulation of food and wider consumer product standards. It is therefore not clear that CPTPP provisions would be consistent with the UK’s food and technical regulations – an issue that it is crucial the Government can provide reassurance on. The SPS chapter promotes the recognition of equivalence based on achieving the same level of protection or measures which have the same effect in achieving the objectives as the importing party’s measure. Chapter 6 focuses on technical barriers to trade (TBT) including conformity assessment and participation of the parties ‘on terms no less favourable than those that it accords to its own persons’ in the development of each other’s technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment procedures. The TBT chapter also refers to the role of international standards, guidelines and recommendations in supporting greater regulatory alignment, good regulatory practice and reducing unnecessary barriers to trade. But UK standards are often higher than international standards and so they may not be an appropriate baseline. It is therefore crucial that the UK Government does not sign up to provisions that lead to a weakening of our standards, or limit how we can apply them to imports.

The Government has also recently consulted on trade negotiations with India [13]. Here again, the UK will be dealing with a country with a very different framework of regulations and standards, including what is within national and regional control. But standards and non-tariff barriers to trade are likely to be a large focus of the trade talks, given that the UK will be seeking to secure tariff reductions from India to improve access for UK exporters to the Indian market, while starting from a comparatively low level of tariffs itself. The UK’s average tariff is 4.2%, compared to India’s average of 14.6%. 60% of Indian exports to the UK are already tariff-free, but only 3% of UK exports to India are. 6% of goods to the UK have a tariff above 15%, but 23% of UK exports to India do. This, therefore, means that non-tariff barriers will be a focus of negotiations. It is important that the Government does not compromise on the UK’s food and product standards or regulations, including by agreeing to recognition of equivalence.

What needs to be ensured now

The Government must demonstrate through the ongoing negotiations that it will stick strongly to its commitments not to compromise on UK standards and consumer protections.

- The FSA and FSS need to play a more central role in ensuring that consumer interests are taken into account and upheld in relation to food standards – including where standards and the level of protection consumers expect may relate to factors that go beyond a scientific risk assessment, such as ethical issues.

- The Trade and Agriculture Commission, given its important role assessing trade deals against UK standards, must have stronger consumer interest representation.

- The Government should also support the recommendations within Henry Dimbleby’s National Food Strategy proposals and set out the core environmental and animal welfare standards that underpin its approach to trade negotiations, which it needs to commit to uphold, alongside food safety. There also needs to be a mechanism for how these will be applied. Our consumer research shows clearly that the vast majority of consumers do not support the use of a dual tariff approach and want standards applied to all imports.

- The Government needs to ensure that any provisions relating to recognition of equivalence of standards or conformity assessment – either directly within trade deals or through subsequent mechanisms that they establish – will not weaken UK standards for imported food and consumer products or prevent future raising of regulatory levels.

Environmental protection

Another of the four priorities identified in the NTC was to ‘protect the environment’. Participants wanted trade deals to help them minimise the environmental impacts of what they buy. People were also concerned by the carbon footprint of international trade, and they welcomed the specific focus by some countries on incorporating environmental protection into negotiating priorities. Participants wanted to see that the UK’s trade deals align with our environmental and sustainability targets.

One of the most striking findings of our online community was the proportion of people who felt this priority was more important in 2021 compared to their view just one year previously. In the NTC in 2020, some participants felt that protecting the environment was a ‘nice to have’ priority, accepting that there would inevitably be some impact on the environment if consumers were to experience some of the benefits of increased trade. However, in 2021, participants felt combating climate change had rapidly increased in importance. With the number of extreme weather events increasing over the past 12 months, many felt urgent action was needed to protect the environment. Considering the impact on the environment of international trade was therefore viewed as a moral responsibility, especially when trading with partners a significant distance away from the UK.

‘I think it’s very important to protect the environment, more than I did last year for sure. This year we’ve witnessed many global catastrophes as a result of climate change, and the shocking scenes seen on our screens has really made me more conscious than ever as to what’s happening.’

- Female, 55–54, South Wales

‘It is a priority, even more so now we have left the EU and are trading less with our neighbours.’

- Female, 45–54, East Coast of Scotland

11 of the 37 participants in our 2021 online community said that protecting the environment was the most important of the four consumer priorities identified as part of the NTC. This priority had the second highest number of votes for being the most important.

‘It is very important for us all to make changes to protect our environment – global warming is a disaster that will affect every person in the world. We can no longer pretend everything will be okay if we recycle a few bits of plastic. Change needs to happen now and permanently for our future and future generations. The longer-term cost of not acting swiftly will outweigh any profits or any costs that could be saved. The government needs to make long-lasting changes no matter the costs for our future and our children’s future. The UK should be a world leader in changing its environmental policies for the good of the country and the world.’

- Female, 45-54, South Wales

‘If we don’t have a functioning planet then none of the other things matter.’

- Male, 25-34, Southern England

The importance of including environmental protections in trade deals was also highlighted in our June 2021 survey. 80% of survey respondents agreed that the UK Government should promote trading in ways that reduce global carbon emissions which contribute to climate change, while 81% agreed that the UK Government’s trade policy should promote high environmental standards – the Government should not sign deals that remove existing environmental protections. However, while survey respondents felt action on the environment was important, many also felt sceptical that the Government would act on this issue. Only 5% of respondents were ‘very confident’ that the UK Government will prioritise environmental protections as part of trade deals, with nearly a quarter (23%) saying they were ‘not at all confident [14]’.

Consumer perceptions of the UK Government prioritising environmental protections

In our 2021 online community, we showed participants information about the environmental commitments and potential impacts of both the UK-Japan CEPA and the agreement in principle (AIP) between the UK and Australia.

There was a mixed response to the evidence presented about the UK-Japan CEPA. Some felt that the marginal impacts on the environment as highlighted by the UK Government impact assessment were positive. Others felt it was a missed opportunity to collaborate on emission reductions and find efficiencies through a signed trade deal.

‘I am glad that they recognise there may be increases in some emissions as this shows they are taking it into consideration. As it is hard to [ascertain] the actual amount [of] increase it is hard to judge if it will have a negative effect on the environment though.’

- Female, 35–44, Southern England

‘As two of the most technologically advanced countries in the world with large economies, we should be [able] to realise better emissions reductions than this. It doesn’t bode well for trade with less developed countries. The deal itself doesn’t seem to encourage emissions reductions, rather it is relying on technology and energy changes that are happening anyway.’

- Male, 35–44, South Wales

Participants were also shown an extract from the UK-Japan CEPA outlining the environmental commitments made in the deal, in order to prompt a discussion of what things people felt the UK Government should prioritise in future trade agreements. They shared a wide range of ideas, and it is clear people want the Government to consider the environment in every aspect of international trade.

‘I feel they should not necessarily concentrate on one area but on as [many] areas as possible to help the environment.’

- Female, 45–54, South Wales

‘The most important thing is the UK should only trade with other countries who value our environment as much as we do, and want to slow down climate change.’

- Female, 18–24, Southern England

When considering the section on the environment in the UK-Australia agreement in principle, the majority were ambivalent. Some felt the wording was too vague to be meaningful, while others felt the UK hadn’t gone far enough to encourage improvements in Australia’s approach. Many were disappointed with the suggestion that the reference to the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change, had been removed.

‘I would say the above statement reads very well indeed regarding protecting the environment, but almost sounds too good to be true. The reason for this and the part that I don’t like is that the UK has had to give way on some climate change commitments. Perhaps they will have to give way to more in the future.’

- Male, 35–44, East Coast of Scotland

‘It is a bit fluffy. Nothing with any real date or aim. Lots of provisions to commit, to affirm, to encourage. No we will be carbon neutral by type stuff. All really indecisive and no real meat on the bones.’

- Female, 35–44, South England

Overall, consumers want to see the UK Government make real commitments to protect the environment. They felt trade agreements and agreements in principle signed so far are not ambitious enough when it comes to the environment. Many want to see the UK become a world leader in areas such as emissions reduction, green energy and sustainable manufacturing, rather than the impact on the environment being considered as an afterthought.

Assessment of progress

In the year that the UK Government has hosted COP26, it is essential that there is a joined-up approach between the Government’s climate change and wider environmental ambitions and its approach to trade. The Government has emphasised that it sees ‘green trade’ as a major opportunity for the UK [15]. It has also stated in its Net Zero Strategy [16] that it will ‘seek to reaffirm our commitment to the Paris Agreement in all UK trade agreements and will ensure that they preserve our regulatory autonomy to pursue our climate targets including our Carbon Budgets, enhanced 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and 2050 net zero commitment.’ The Net Zero Strategy also recognises that ‘decisions on the liberalisation of partners’ goods must account for their environmental and climate impact. Where there is evidence that liberalisation could lead to significant carbon leakage, the case for maintaining tariffs or pursuing conditional market access, through clauses on standards or eco/carbon intensity, should be carefully considered.’

Japan

Chapter 16 of the CEPA agreement with Japan, as with the deal Japan has with the EU, covers trade and sustainable development and as set out above, this was shared with people in our online community. The chapter places an emphasis on co-operation, rather than harmonisation of environmental standards and recognises each other’s right to regulate and adopt their own levels of environmental protection – and that each party should strive to ensure high levels of protection. As in the EU-Japan agreement, the UK and Japan commit that they will not encourage trade or investment by relaxing or lowering their respective levels of environmental protection – but won’t use such measures as a disguised restriction on trade.

The deal also stresses the importance of multilateral environmental agreements and each party agrees to strive to facilitate trade and investment in goods and services of particular relevance to climate change mitigation. It emphasises biodiversity and says that each party will encourage the use of products which are obtained through sustainable use of natural resources. More generally, the parties recognise the importance of ‘reviewing, monitoring and assessing, jointly or individually, the impact of the implementation of this agreement on sustainable development through their respective processes and institutions, as well as those set up under this agreement.’

An impact assessment of the deal was prepared by the UK Government and presented to Parliament. This concluded that the agreement was not expected to have significant impacts on greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), energy usage, trade-related transport emissions and wider environmental impacts such as air quality, biodiversity and water use or quality. It estimated that it would increase domestic GHG emissions marginally, dependent on the measures the Government implements to achieve net zero by 2050. It could also benefit services sectors, such as environmental engineering and consultancy.

Australia and New Zealand

Based on the AIPs, the deals with Australia and New Zealand will include similar provisions, but, particularly in the case of New Zealand, these will be more comprehensive.

Australia

In what was seen as a major achievement by the UK Government for the first time Australia committed to specific mentions of the Paris Agreement in a free trade agreement. The AIP states that Australia and the UK both affirm commitments under multilateral environmental agreements and agree to effectively enforce domestic environmental laws and policies across a broad range of issues. It also includes commitments to encourage trade and investment in environmental goods and services and co-operation on green technologies.

There have, however, been reports that the UK may have been willing to remove some of the key climate change pledges from the final text of the trade deal in order to agree on other provisions. The Government has however stressed that the agreement will include a firm commitment from both parties to the Paris Agreement goals [17].

New Zealand

The AIP with New Zealand commits the two countries to an ambitious chapter that will support both of their trade and environment agendas and responses to the urgent threat of climate change. It states that the chapter will, for example, preserve New Zealand and the UK’s right to regulate to meet their respective climate action targets and wider environmental objectives, and recognise that nothing in the agreement will prevent either from fulfilling their commitments under the Paris Agreement. The two countries also affirm their commitments to tackling climate change and strengthening the global response. They commit to promoting trade and investment in environmental goods and services which support the transition to a low carbon economy and co-operation on carbon markets and pricing, including ‘the most comprehensive list of environmental goods agreed to date’ with tariff elimination when the agreement comes into effect for these environmentally beneficial products.

The AIP trails ‘precedent-setting’ commitments on environmentally harmful subsidies, clean energy and sustainable trade to ‘transition away from fossil fuels, including ending unabated coal-fired electricity generation, and taking steps to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies where they exist with limited exceptions in support of legitimate public policy objectives’ and address inadequate fisheries management. For both the Australia and new Zealand deals, the commitments are still limited mainly to cooperation and statement of ambitions.

Other trade deals

The relative priority of environmental provisions within the other trade deals the Government has prioritised is likely to vary greatly depending on the other party. The UK Government has consulted, for example, on going beyond the continuity agreement that has so far been agreed with Canada. But this may be more difficult with the Gulf Cooperation Council and countries such as India.

Chapter 20 of the CPTPP focuses on the environment and includes commitments to promote mutually supportive trade and environmental policies, high levels of environmental protection and effective enforcement of environmental laws. It also recognises that multilateral environmental agreements play an important role – but again has limited proactive commitments.

As well as the specific environmental chapters within trade deals, the implications of the other chapters, including access for goods and services and TBT and SPS provisions, will also be crucial in determining how the UK can regulate (for example, in areas such as ecodesign regulations and other relevant standards) and what the deal will mean in terms of actual trade flows. As set out in the standards section above, in addition to the impact of the actual trade, how products have been produced and the overall contribution they make to carbon emissions will be crucial. The extent to which imports complement or contradict domestic measures to drive more sustainable production and consumption is pivotal too.

What needs to be ensured now

The UK Government must build on its leadership role at COP26 and be a global leader in promoting trade that supports its climate and wider ambitions.

- Environmental protection and tackling climate change must be a central pillar of all new trade deals, and the deals that the Government signs must support the UK’s transition and not undermine it.

- The Government must conduct a full environmental impact assessment to understand the implications of any trade deals on its net zero commitments, as well as other environmental impacts before deals are finalised.

- All chapters across a trade deal must be carefully assessed from an environmental protection perspective in order to ensure that they will support the UK’s ability to meet its net zero ambitions. This includes, for example, ensuring that climate friendly regulations will not be obstructed and linking tariff reductions to environmental commitments. They should also not result in trade flows that will undermine or undercut national initiatives to drive sustainability goals.

- The Government should report annually on progress that has been made through cooperation provisions within its FTAs.

Data protection and digital rights

Another key consumer priority identified by our NTC participants was ‘Maintain data protection regulations that protect consumer rights’. Participants could see the economic opportunities of digital trade, however, there were also widely held concerns about what the potential implications of measures intended to deliver smoother digital trade by enabling free data flows would be for the protection of consumer data and online rights.

When the NTC took place in 2020, participants had only been experiencing the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic for a few months. Those who took part in our online community in 2021 had experienced the pandemic for over a year, and this context was noticeable in their discussions of this priority. For many, the importance of maintaining digital rights and protections was even more important a year on, given that the pandemic has resulted in us leading much more of our lives online. Many participants also felt the rate of online scams had increased since the pandemic began. More widely, participants also cited data breach scandals and media coverage of data misuse as contributing factors in the increased importance of the UK Government not trading away the high standard of existing protections in future agreements.

‘Digital protections have been a higher priority in my eyes due to the huge rise of online fraud and scams during the pandemic.’

- Male, 45–54, South Wales

‘[This priority is] definitely more [important]. Since last year I’ve become more aware of how monopolised digital space is. Recent Ireland indemnity of Facebook for WhatsApp privacy breaches demonstrate that these big tech firms can’t be trusted to self-regulate. It is an unenviable task to gain control over digital space... Sovereignty gained from Brexit should be put to good use here – frittering it away in order to secure favourable tech trade deals with more lax countries would be a mistake.’

- Male, 25–34, Southern England

Our survey in June 2021 found consumers were in agreement about the importance of maintaining stringent data and digital protection for UK consumers. 88% thought it was important that any future trade deals should not reduce the level of data and digital protection for UK consumers – with nearly two thirds (63%) saying this was ‘very important’.

The discussions of this priority in our online community centred around what the Government has agreed as part of the UK-Japan CEPA and, in general, participants were rather disappointed. While a small proportion were pleased with the benefits the deal could bring to the UK digital and financial services markets, many participants were apprehensive about the terms of the trade deal and felt the Government had compromised on this priority in order to get the agreement signed. There was widespread concern about certain elements of the deal, especially the validation of voluntary self-regulation and the precedent this deal could set for future agreements. The risk of data being transferred out of Japan to the USA (highlighted by the Open Rights Group [18] and shown to participants within the community) was particularly concerning.

‘It seems the deal is great for business, not so good for consumers. As a consumer the flow of information from Japan would be a worry. I feel the deal was not fully thought through and the voice of business has drowned the voice of [the] consumer.’

- Female, 55–64, Northern England

‘The idea of my data freely flowing to the US displeases [me] greatly as well – a US deal through the back door.’

- Female, 45–54, Southern England

Participants were unconvinced by the UK-Japan CEPA data protection explainer [19] published by the Department of International Trade. They felt the language used was insufficiently precise and focused on combating negative views of the deal, instead of highlighting any consumer benefits.

‘I think they are going over the top to keep on trying to persuade us that this deal poses zero risk to our data privacy and digital security. It feels a bit like they’re protesting too loudly... I think that they’ve put this out because there are justified concerns about the risk which comes with the deal.’

- Female, 35–44, South Wales

Overall, participants were very aware of how much of their lives are lived online and the impact that data security and privacy has on them. While they were unconvinced by the terms of the UK-Japan CEPA, they were hopeful that the UK Government would take this priority more seriously in future trade negotiations and ensure the consumer perspective is accounted for.

‘Whether we like it or not, we live in a digital age. The vast majority of us give our details daily to companies that we deal with and probably think nothing of it. Any new trade deal has to be very strict on how this data is dealt with... Data exchange can be very useful in trade, but the balance has to be right... Consumers being protected must be paramount.’

- Male, 55–64, South Wales

Assessment of progress

The digital chapters of trade agreements are becoming increasingly important and high profile given the important role the online world plays in our everyday lives.

This is an important issue for consumers as more purchases move online and data-gathering digital technology becomes embedded in all kinds of everyday goods, from fridges to vacuum cleaners. Without strong data protection measures, consumers’ data could potentially be collected, shared and used in ways that they did not consent to or expect.

It is important to ensure strong data protection both domestically, through the review of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that the Government has begun, and also through the UK’s international trade commitments, for when UK consumers’ data flows abroad.

Trade rules on cross-border data transfers should facilitate trusted data flows while ensuring the highest level of data protection and privacy for consumers by retaining full autonomy for the UK to regulate for personal data protection. References to data protection in trade agreements could be detrimental to UK consumers if the language introduces flexibility into the well-regulated UK system by promoting interoperability or compatibility with weaker international rules for data transfers without additional safeguards.

In September, the Government published over-arching digital trade objectives [20] which focused on securing ‘access for British businesses to overseas digital markets, so that firms can invest and operate across borders freely and in fair competition.’

Positively, consumer safeguards are included as a part of the five pillars the Government states it is focusing on to deliver its vision, recognising that the success of the UK’s digital trade policy is heavily dependent on the impact it has on consumers, alongside businesses.

Another welcome objective is the Government’s intention to ‘advance digital consumer rights, such as seeking access to redress and reducing spam (unsolicited commercial electronic messages) under consumer and business safeguards.’ Consumers face many direct challenges when they buy online, especially from sellers located abroad – these include unexpected costs, scams and the sale of unsafe products. Addressing these harms by advancing consumer rights and collaborating with trade partners to tackle challenges posed by new business models, such as online platforms and online harms more generally, should be included within trade deals. Access to redress through international cooperation and trade commitments would help to enhance consumer trust online. Trade deals should also deliver concrete consumer benefits, such as cheaper data roaming.

However, the UK Government has also stated the intention to ‘encourage the interoperability of digital standards and frameworks globally to maximise the opportunities and benefits of digital trade'. It is crucial that the impact on consumers is also a central consideration here. Interoperability between different digital standards and systems, specifically when it comes to data flows, should not come at the expense of maintaining the UK’s current high standards of data protection. Existing mechanisms that promote compatibility, such as data adequacy agreements and specific alternative transfer mechanisms, ensure consumers can rely on the fact that businesses operating in the jurisdictions of trade partners are adhering to the same standards of protection that they enjoy domestically.

Introducing language in trade texts and commitments that blur the lines between strong and weaker data protection regimes should therefore be avoided. Promoting interoperability with international standards that offer weaker data protection than the UK’s current domestic regulation should also be avoided to ensure the highest possible protection for consumers and prevent the introduction of flexibility into a well-regulated system – and also provides certainty for businesses.