Decoy offers and consumer choice

Executive Summary

The choice architecture in online markets influences consumer decisions and interfaces can be designed in ways to either help or harm consumers. One tactic to malignly influence consumer choices is the use of decoys, which are options individuals would not rationally choose but which make other options more attractive. These have been shown to manipulate customers to purchase more expensive options. In a recent review of online choice architecture practices, the Competition and Markets Authority identified the use of decoys as a practice which is almost always harmful to consumers.

In this policy research report, we present the findings of an online experiment investigating the effect of decoy options in the context of home broadband packages. We chose the home broadband market following desktop research that found it was fairly common for telecoms providers to offer broadband packages that may act as decoy options.

In our experiment, decoys can be either dominated or close. A dominated decoy is an option that is the same or inferior to another in all attributes, so that no rational consumer should choose it. In terms of broadband services, this could be a package with the same price as another package from the same provider but a slower download speed. A close decoy is not dominated by another option, but offers relatively poor value for money. For example, a broadband package with a small price reduction for a substantial reduction in download speed compared to another from the same provider.

There has been no previous research exploring decoys in this market. Therefore, our main research question is to what extent decoys affect people’s choices in the broadband market. Our experiment explores two further research questions. First, how does the decoy effect vary when consumers are presented with different numbers of options. Second, to what extent does the effect change when the decoy is a close rather than a dominated option.

Using a nationally-representative sample of more than 4,000 consumers, we found that the presence of a decoy had a substantial effect on the choice of broadband package. Overall, more than one in six participants (17%) switched to a higher priced broadband package when shown a decoy compared to their choice with no decoy present, see Figure 1.

The decoy influenced choices in all circumstances we tested. However, it had a greater effect when participants were shown just three broadband options rather than five, and when the decoy option was dominated by another option rather than a close decoy that offered a considerably slower download speed for just a £1 reduction in price. This meant the effect of the decoy varied across experimental treatment groups, but was strongest when participants were shown just three options and a dominated decoy.

Figure 1: The effect of the decoy varied across treatment groups

Source: Yonder on behalf of Which? surveyed a nationally representative sample of people online. Each treatment was seen by two groups with 6,312 observations in total. Sample sizes are as follows: 3 options, close decoy 1594, 5 options, close decoy 1562, 3 options, dominated decoy 1594 and 5 options, dominated decoy 1562. Percentages are unweighted.

Our findings show that the use of decoy options can lead to people choosing a more expensive option, causing financial harm. In our experimental setting, this means they would spend between £36 and £120 per annum more on their home broadband. [1]

Policy implications and recommendations

The findings have implications for the optimal way to regulate against the use of decoys. Currently, enforcers of consumer law would need to rely on the general legislative provisions that protect consumers from unfair trading. [2] This could include the prohibitions against misleading actions or misleading omissions, or a contravention of the requirements of professional diligence, but enforcement on the basis of any of these may be difficult. A prohibition on the use of dominated decoys by adding them to the list of commercial practices which are in all circumstances considered unfair (Schedule 20 of the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024) would send a clear signal that decoys are harmful to consumers, be relatively easy to enforce and have a strong deterrent effect compared to other types of regulations. However, such a ban could potentially be circumvented by the use of close decoys, so it would be insufficient to stop consumer harm.

The harm from manipulative decoys could be prevented through the use of outcomes-based regulation. In the UK, this would only be possible for financial services and, potentially, the largest tech firms, but not a telecoms market like the one in which our experiment is set. However, Ofcom, the sectoral regulator, has developed a set of voluntary ‘Fairness for Customer’ commitments to strengthen how companies treat their customers. Our evidence suggests that the use of decoys by communications providers is in tension with these voluntary obligations since decoys can induce consumers to purchase services that are beyond their needs. We therefore expect Ofcom to challenge firms that market decoy options to demonstrate that their use does not break the commitments.

1. Introduction

While online markets offer many benefits to consumers, one of the downsides is the increased opportunity for businesses to manipulate consumer choices to produce outcomes that favour the business, but leave customers worse off. While manipulative behaviour has always been a feature of markets and there have long been consumer protections to regulate unfair trading practices, businesses in online markets have greater control over the consumer journey and some routinely employ online choice architecture (OCA) to exploit their customers’ psychological vulnerabilities or cognitive biases.

There are various ways in which businesses might use OCA to manipulate choices. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) helpfully identifies 21 different OCA practices that affect the way in which choices are structured, the way information about choices is presented or how pressure might be applied to those making choices. Not all OCA is harmful and ethical design can benefit consumers, but when used malignly it can lead to consumer detriment.

One practice identified by the CMA as being almost always harmful is the use of decoy choices. These are additional options in a choice set that few or any customers would rationally choose, but which alter the attractiveness of other options. They are typically used to steer consumers towards a higher-priced target option. This can be done either by including a decoy that is even more expensive than the target option so it makes it appear to be relatively good value, or by including a similarly-priced option which is inferior in other attributes, such as quality. In either case, the potential harm from the use of decoys is clear; by inducing a customer to buy a more expensive option that they would have chosen if there was no decoy then the decoy causes financial harm.

In this research paper, we present experimental evidence of the impact of decoy options on consumer choices for home broadband packages. Using a nationally-representative sample of 4,036 broadband customers we first elicit their preferences for speed and monthly price and then test whether this changes in the presence of a decoy option.

We chose to set the experiment in the context of the home broadband market following a review of markets in which we suspected businesses would be more likely to use decoys. We reviewed service based products, commonly bought through digital channels which have attributes which providers can easily adjust. These attributes offer businesses the capability to offer a menu of different options with various combinations of different attributes. We found many potential decoys across a variety of industries including broadband and mobile phone contracts, online game subscriptions and gym passes, but they were particularly prevalent in the broadband market, see Annex A.

We found numerous cases of offers in the broadband market that were inferior to (dominated by) another option and which no rational consumer would buy. They were broadband packages with the same or higher monthly price as another package but with a slower download and upload speed.[3] An example of this is shown in Figure 2 with broadband packages offered by the firm Plusnet in August 2023. The Full Fibre 300 is dominated by the Full Fibre 500 option, being identical in every respect except for slower minimum guaranteed download and estimated upload speeds. Dominated decoys are easy to identify, but we also found firms offering broadband packages that while not dominated might create a decoy effect because the price difference was small compared to a large difference in download speed, see Table A2.

Figure 2: Decoys in Plusnet broadband options

Source: Plusnet broadband options displayed for a UK address with full fibre capability, seen in August 2023.

The broadband setting for our research is novel, but our experimental research also extends the existing research literature by varying the choice set size and by comparing the effect of the decoy when it is a dominated option, i.e. objectively inferior because it is no better than the target in any attribute, to the effect of a close decoy, a lower-priced but poor value option. These are important factors because they matter for determining whether there is a need to specifically regulate against the use of decoys and, if yes, the optimal way to do this.

2. Decoys: Theory and evidence

If consumers were entirely rational then choices would be independent of irrelevant alternatives, so that decoys would not change consumer behaviour. However, in practice, CMA concluded that decoys are almost always harmful because they can make some attributes of a product more salient, which can manipulate consumers to choose a target option that is not best-suited to their needs. This can cause financial harm if a consumer spends more than they would have done in absence of a decoy option.

Decoy options can create a range of effects, most commonly attraction and compromise effects. An attraction effect could be created by a business introducing an ‘inferior decoy’ that makes the alternative, target option more attractive and increases the likelihood of it being purchased. By contrast, a compromise effect can be created by offering an extreme option that makes the target option look more desirable, for example a high priced decoy might increase subjective valuations of a more modestly-priced target option that is now in the middle of the range of options. The presence of the more expensive option may help consumers to justify a purchase decision, especially if they are prone to being risk averse.[4]

In this research, we focus on the attraction effect created by an inferior decoy, which are the types of decoys observed in the broadband market. [5] Most obviously, these can be asymmetrically dominated decoys that are only inferior to the target option, although they might not be inferior to other options available to consumers. This is illustrated in Figure 3 with just two attributes, price and quality. The target option is a relatively high price, high quality option compared to the cheaper alternative (labelled the ‘competitor’ option in the terminology of the decoy effect) that the business wants to steer a customer away from. The orange box shows the set of all decoy options that are asymmetrically dominated in relation to the target option, ie all of the possible combinations that are the same price or higher for a level of quality that is no greater than the target. The example decoy, DD for dominated decoy, is the same price as the target, but lower quality. No rational consumer should choose the decoy over the target, although they may prefer it to the competitor.

Figure 3: Attribute space for dominated decoy options

Source: adapted from Weinmann et al, 2021.

An option does not need to be dominated to be a decoy that creates an attraction effect. This could happen if the decoy is a lower price than the target, but the price difference is small relative to a large gain in quality. An example of this shown in Figure 3 by the point CD. We refer to these options which are close in one attribute but with a large difference in another attribute as ‘close’ decoys.

A significant amount of prior research on decoys based on discrete choice experiments [6] has found decoys creating an attraction effect in a wide array of products, including: films, cars, beer, insurance and crowdfunding. There has been little research on the effects of decoys in real world markets, but Wu and Cosguner (2020) find evidence of decoys at an online diamond retailer and estimate these increase the diamond retailer’s profit by 14.3%.

The effect of close decoys has received little attention in the literature. However, some studies have examined a wider range of possible decoy relationships and distance to the target option. These find that a close decoy significantly biases choice towards the target, though the effect is weaker as compared to an inferior decoy. There is also extensive existing literature on the “just noticeable difference”, whereby individuals perceive sufficiently similar attributes as the same, and an effect of “equate to differentiate” describing the choice strategy of explicitly disregarding or ignoring attributes where options have similar values, and focusing only on attributes that differentiate between them.

There is very little published literature that explores the impact of choice set size on the attraction effect. Three options in the choice set with one competitor, one target and one decoy is a classic decoy experiment set-up. One recent publication does explore larger choice sets and finds that the size of the decoy effect diminishes when the number of available options increases. They still find the target is chosen more often than if the participant chooses randomly even with their maximum number of eight alternatives. However, the design does not control for individuals’ preferences in the absence of the decoy, meaning that the diminishing effect of the decoy with more options could be explained by the additional options being genuinely preferred. It is often the case that consumers will be shown choice sets larger than three options in our market setting of home broadband, so our experiment therefore examines whether the attraction effect differs if participants see three or five options.

3. Methodology

We designed the experiment in the context of individuals selecting their broadband package and the core objective was to estimate the proportion of consumers who switch to a higher priced target option in the presence of a decoy.

3.1. Survey design

The experiment had two stages. In the first stage, we elicit the participant’s preferred broadband package without decoys using a series of pairwise choices. Then, in the second stage, we elicit the participant’s preferred broadband package in the presence of a decoy. All participants are included in both stages, but the second stage of the experiment is a two by two design splitting the sample into four groups based on whether they see three or five broadband packages and whether they see a dominated or close decoy first. In effect we therefore have four treatment groups and the comparison is made to an individual’s choice in the first stage.

3.1.1. Design of the first stage experiment

The aim of the first stage of the experiment was to uncover the participants preferred broadband package without a decoy. To do this we presented them with a series of pairwise choices between broadband packages. These packages were based on the average monthly cost of packages with similar speeds found during our desktop research, details of which can be found in Annex A, Table A3. The other attributes, set-up cost and contract length remained constant across all packages. The possible broadband choices for the first stage are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Possible broadband options in the first stage

To determine the participant’s point of indifference we give them dichotomous choices of adjacent speeds, for example 67Mbps versus 150Mbps as shown in Figure 4. We did not include other design features in the presentation of the broadband choices such as false hierarchy. [7] Excluding other design features isolates the impact of the decoy on the participants' decisions.

Figure 4: Screenshot of first stage choice between 67Mbps and 150Mbps

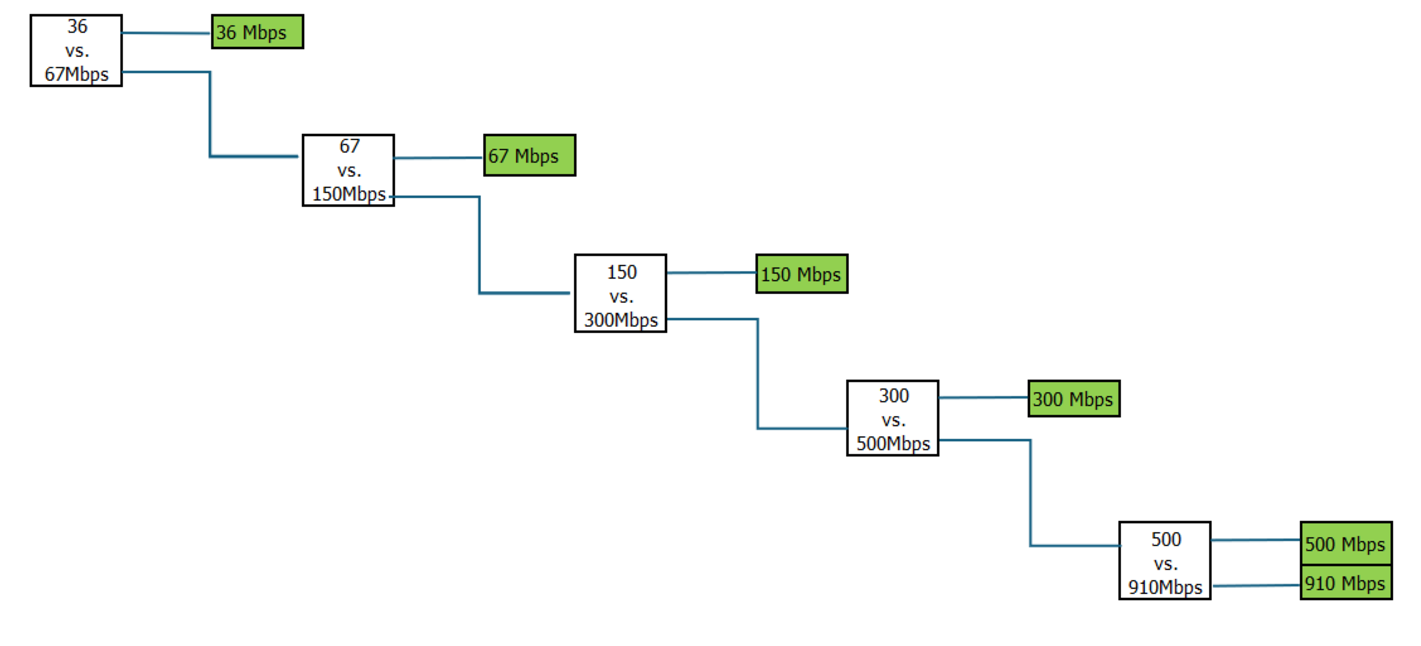

The number of dichotomous choices the participant saw in the first stage of the experiment depended on their decisions. Some participants saw only one dichotomous choice and others saw up to five choices. Figure 5 shows the decision tree for a participant with a starting point of 36 versus 67Mbps.

Figure 5: Decision tree for a participant starting with 36Mbps versus 67Mbps

The white boxes denote choices, and the green boxes denote the participant’s final speed selection and when the first stage ends. Starting off with the 36 versus 67Mbps choice, if the participant prefers the 36Mbps the first stage ends as there are no slower options available. If however the participant prefers 67Mbps, they also need to confirm they prefer this to the next highest option, 150Mbps, before 67Mbps is confirmed as their original preference speed.

The starting point in this first stage could have an anchoring effect. If all individuals were shown the lowest possible starting point, 36 versus 67Mbps this may bias preferences towards slower and cheaper options. On the other hand, if all individuals were shown the highest possible starting point, 500 versus 910Mbps this may bias preferences towards faster and more expensive options. To account for this, we randomised the starting point, with a least-fill approach to ensure that there was a sufficient sample size among all starting points. There are five possible starting points: 36 versus 67Mbps, 67 versus 150Mbps, 150 versus 300Mbps, 300 versus 500Mbps and 500 versus 910Mbps.

3.1.2. Design of the second stage experiment

In the second stage of the experiment we elicit the participant’s preferred broadband package when there is a decoy present. The participant’s preferred package from the first stage of the experiment was fed through into the second stage becoming the competitor option, ie the option that we are trying to steer the consumer away from. The next highest speed option above their preferred first stage selection becomes the target option, ie the option we are trying to steer the consumer towards. We then include an additional speed option between the competitor and target to act as a decoy.

In this second stage, half of participants were given a choice set with just three broadband packages and half saw five packages. Three options with a competitor, decoy and target is a typical set-up for decoy experiments, but in the broadband market companies often present larger choice sets and the number of options may change the impact of a decoy. For the five option choice set, we added a speed slower than their original preference and a faster option above the target. All possible choice sets for the second stage are shown below in Table 2.

Table 2: Second stage speed choices presented given the speed preference in stage one

Note: * denote choices that were not shown to participants in the first stage. Choices in bold italics denote the decoy option and in bold the target option.

We always place the decoy as the middle option in the choice set to avoid any positional bias between the three and five options. The decoy option is a new choice that was not previously presented, but the target option is one which the respondent has declined in stage one. An exception is for participants with a preferred speed of 910Mbps in the first stage, as in this case the target option was not offered in the first stage. This brings the unavoidable complication that the choice of the target speed in stage two may simply reflect a desire for a faster speed and be unrelated to the presence of the decoy. We also have to introduce a new option as the slowest speed in the five option choice set for those choosing 36Mbps in stage one. Again this means that those choosing this option may do so with a genuine preference that was not satisfied in stage one, but given this would bias downwards the effect of the decoy then we are less concerned by this.

Our desktop review of broadband providers also found that consumers were sometimes presented with options with a relatively small price difference for a relatively large gain in download speed. These are asymmetrically-dominated decoys, but such close options may still create an attraction effect. To test this, the participants were given two rounds of choices, one round had a choice set that contained a dominated decoy and the other had a close decoy priced £1 below the monthly cost of the target option. Half of the participants were shown the dominated decoy first and the others saw the close decoy first. All the decoy prices are presented in Table 3 below.

Table 3: Decoy broadband package options

The second stage of the experiment is a two by two design with four treatment groups, which are listed below in Table 4. Two groups were given choice sets with three options and the other two were shown choice sets with five options. Each participant was given the same sized choice set for both of their rounds.

Table 4: Experiment second stage treatment groups

Participants were randomly assigned to each of the treatment groups using a least fill approach. Each treatment group had over 1000 participants.

3.2. Questionnaire structure

The full survey questionnaire was structured as follows:

- Question on responsibility for their mobile and broadband service - participants not at least partially responsible for their broadband service were screened out at this stage.

- Questions on age, gender and employment to ensure a nationally representative sample of UK adults 18+.

- First stage experiment section.

- Survey questions to understand the respondent’s previous engagement with broadband choices, as more experienced purchasers may be less susceptible to being influenced by a decoy. These questions also served as a buffer between the two stages of the choice experiment to reduce the likelihood that choices in the second stage would be influenced by having just answered a similar question. The questions were:

- When they last changed their broadband contract

- How they obtained their broadband contract

- Whether they found it easy to find a broadband deal that fits their needs

- Whether they have ever haggled for a broadband deal

- Second stage experiment section with two rounds of choices.

- Additional survey questions to understand the respondent’s demand for broadband and which we could subsequently use to explore whether usage might affect the likelihood of being influenced by a decoy. These questions were:

- Their current broadband package (provider, contract length, monthly cost, download speed)

- How many other people regularly use their household’s broadband

- Regular online activities

- Connected devices

- Whether they had experienced any problems with their broadband service

- Demographic questions on education, disability and household income.

3.3. Pilot testing

An initial pilot was conducted with a non-representative sample of 199 UK residents using the Prolific platform. In this initial pilot, a high proportion of individuals selected the highest speed of 910Mbps, see Table 5.

Table 5: Distribution of preferred broadband speeds without decoys, Prolific Pilot

Source: University of Warwick on behalf of Which? surveyed a non-representative sample of 199 observations online using the Prolific platform. Percentages in brackets, unweighted.

So many participants selecting the highest speed is not ideal as for that subset we cannot be certain that choosing the target option in the second stage is only due to the decoy. To ensure a better spread of preferences we increased the monthly cost of the 910Mbps from £45 to £50 per month and tested this in a second pilot study.

The second pilot of a further 209 participants was conducted by Yonder and found no bias towards higher speeds. We made no major adjustments between the second pilot and the main survey, thus we incorporated results from the second pilot with the main survey.

3.4. Survey administration

The main fieldwork took place between 12th June to 17th June 2024 with a further 3,827 observations giving a total of 4,036. Both samples were sourced from Yonder’s online panel. Using a least fill approach to randomly allocate participants to a starting choice in the first stage of the experiment meant that each starting point had at least 805 participants. The same approach to the second stage meant that each treatment had at least 1,008 participants.

3.5. Analysis samples and exclusions

As highlighted in section 3.3, participants with a preferred speed of 910Mbps and then selected the target option in the second stage may simply reflect a desire for faster speed and be unrelated to the presence of the decoy. Therefore, these participants are removed from our preferred analysis sample. Participants with outlier reaction times were also removed from our preferred analysis sample, this is a common exclusion in economic experiments.

The full sample is all participants with their choices at rounds one and two at Stage 2 pooled, this equates to 4,036 participants and 8,072 observations. However, our preferred analysis sample has 3,156 participants and 6,312 observations after making the following exclusions:

- First, we remove participants with the fastest 2.5% and slowest 2.5% of average response times in the first stage of the experiment. This equates to 2 seconds and 60 seconds per screen and for consistency we remove any participants equal to these thresholds. This leads to the exclusion of 217 participants.

- Second, those choosing a preferred speed of 910Mbps in stage one are omitted because it is impossible to determine whether the choice of the target option in stage two of the experiment is due to the presence of the decoy or a preference for a higher speed that was unsatiated in the first stage.

4. The experiment findings

4.1. First stage speed preferences

In the first stage of the experiment, participants were presented a set of dichotomous choices to determine their preferred broadband speed from a range: 36Mbps, 67Mbps, 150Mbps, 300Mbps, 500Mbps and 910Mbps. The distribution of the preferred speeds from the first stage of the experiment are shown in Table 6 with the full sample of 4,306 participants and our preferred sample after exclusions with 3,156 participants.

Table 6: Distribution of preferred broadband speeds without decoys, main survey

Source: Yonder on behalf of Which? surveyed a nationally representative sample of 4,036 people online. Percentages in brackets, unweighted. Our preferred sample has 3,156 participants after exclusions.

Comparing the distribution of the original preference speed by the participant’s assigned starting point, see Annex C Figure C1, there is a bias in preferred speeds towards the randomly assigned starting point. However, the randomised, least-fill approach to allocating participants to starting choices means that there is a plausibly even spread of participants across choices overall.

4.2. Second stage choices with decoys

As discussed earlier, the second stage had four treatment groups, based on whether they were given a choice set with three options or five options and whether they saw a close or dominated decoy first. A least fill approach was again used to assign participants to treatment groups and there was no statistical dependence between the final speed selection in the first stage and the assigned treatment group, as illustrated in Figure C2 in Annex C. We personalised the second stage choice sets based on their original preference speed without decoys. Therefore, every participant becomes part of the control group and the key outcome variable is the proportion of participants who select the target broadband package, which they had previously declined in the first stage, in the presence of a decoy.

Table 7 shows the proportion who selected the target, decoy or original choice from the second stage of the experiment across all possible choice sets, but only where participants given the five option choice set were able to select a slower or faster speed. The results are presented for four samples of participants: full sample, preferred sample and round 1 and 2 separately for the preferred sample.

The final two columns of Table 7 present the choices for round one and round two separately for the sample after exclusions. It shows that participants were less likely to move away from their stage one choice and choose the target in round one, but the reason for this is unknown. It may be that recollection of the stage one choice acts as a restraint on the decoy effect with participants wanting to be consistent with their previous choice, but this becomes weaker as the respondent progresses through the experiment and recollection fades. In any case, we have no strong rationale to favour either the round one or round two choices over the pooled data, so we henceforth focus on the pooled preferred sample.

Each group (Table 4) saw two choice sets, we checked whether there was a difference between the first and second choice sets. These results are shown in Table 7. A statistically significant higher proportion of participants select the target option in round two with fewer participants sticking with their original choice. The proportion choosing the decoy remains the same between rounds.

Table 7: Distribution of second stage choices

Source: Yonder on behalf of Which? surveyed a nationally representative sample of 4,036 people online. With two rounds this gives a full sample of 8,072 and 6,312 observations after exclusions, with each round containing 3,156 observations after exclusions. Percentages are unweighted. * Lower and higher value options could only be chosen by the half of the sample that were given a choice set with five options.

In our preferred sample, participants stick with the option they chose in stage one of the experiment in more than two-thirds of choices. However, in 17% of cases they choose the target option, which is an option they declined when presented in a pairwise comparison.

The target option is more likely to be selected when the participants are presented with the smaller choice set with three options as opposed to five, as shown in Figure 6. The target was also, unsurprisingly, more likely to be chosen in the presence of a dominated decoy rather than a close decoy, although an attraction effect was still evident with the close decoy. Almost one in four (24%) participants chose the target when shown only three options and a dominated decoy, but was just 11% for five options and a close decoy.

Figure 6: Likelihood of choosing the target option by treatment

Source: Yonder on behalf of Which? surveyed a nationally representative sample. Percentages in brackets, unweighted. Each treatment was seen by two groups (Table 4), with 6,312 observations in total. Sample sizes are as follows: 3 options, close decoy 1594, 5 options, close decoy 1562, 3 options, dominated decoy 1594 and 5 options, dominated decoy 1562.

Some respondents in all treatment groups chose the decoy, even when this was a dominated choice. However, almost twice as many chose it when offered a close decoy, reflecting that this may be a legitimate choice that best fits their preferences.

We did not find any obvious relationship between the speed the participant chose in the first stage and their likelihood of switching to the target, as shown in Figures 7a and 7b. For the three option choice set the proportion choosing the target option varies somewhat by speed, but without any pattern in the variation. By contrast the results for the five option choice set are very consistent. A smaller proportion chose the target option when their original speed was 36Mbps, but we expected this to be lower because for this group the lower-priced, slower speed of 11Mbps only became available in round two and so this might reflect genuine preferences for a cheaper, slower package.

Figure 7a: Choice by original preference speed - 3 options

Source: Yonder on behalf of Which? surveyed a nationally representative sample. Total observations seeing three options in the second stage is 3,188 observations. Sample sizes 36Mbps 528, 67Mbps 422, 150Mbps 946, 300Mbps 732, 500Mbps 560

Figure 7b: Choice by original preference speed - 5 options

Source: Yonder on behalf of Which? surveyed a nationally representative sample. Total observations seeing five options in the second stage is 3,124 observations. Sample sizes 36Mbps 538, 67Mbps 368, 150Mbps 882, 300Mbps 740, 500Mbps 596.

To understand how different variables impact the likelihood of selecting the target option, we conducted a logit regression with a binary dependent variable for whether the participant selected the target in the second stage of the experiment. The model and the results are presented in Annex C. Briefly, the regression results support the unconditional analysis: respondents are statistically significantly more likely to choose the target option in the three option choice set and with a dominated rather than a close decoy.

The regression analysis also finds that the effect of the decoy is statistically significantly stronger for larger households that have 3, 4 or 5 people using the broadband at once compared to 1 person, and when the participant uses their broadband for a higher number of medium-high use activities such as video conference calls. There were no clear differences in the effect of the decoy by demographic characteristics.

5. Discussion

Our experiment provides three main findings. First, it provides further evidence, complementing the existing academic literature, that decoy options can have a large effect on consumer choices, in this case in the context of choosing a home broadband package. The one in six people who chose a higher-priced broadband package, which they had previously declined when offered in a simpler choice setting, will suffer harm if this is not in line with their true preferences. In our example scenarios they would be increasing their annual payments by between £36 and £120.

Second, our experiment gives evidence that the attraction effect is present but weaker in larger choice sets, even when explicitly measuring and controlling for individuals’ preferences as measured in an environment where no such biases were present. We have no direct evidence from our experiment design to indicate the causal mechanism for this, but it seems plausible that more options bring greater ‘decision noise’; that any random variation in choice and preference will reduce choice proportions for the target by a larger amount when it is one of five potential options that noisy choices could land upon as compared to being one of three. Individuals may also use different comparison points when given more options, so that overall the comparison between the decoy and the target becomes less salient and the attraction effect is smaller.

Third, we find that while close decoys have a smaller effect than dominated decoys they still increase the likelihood of the target being chosen. This latter finding is important because it raises questions about the optimal way to regulate harmful decoys.

Where specific business practices are known to be unfair and harmful then rules-based regulation that prohibits the use of these practices, such as Schedule 20 of the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 which lists commercial practices which are in all circumstances considered unfair, is likely to be the most efficient way of protecting consumers. This is because these are relatively easy to enforce compared to other types of regulations and should create a strong deterrent effect. However, the fact that close decoys may be both the best option for some consumers and act as a decoy for others raises a challenge for how a prohibition on the use of decoys could be drafted. A ban on asymmetrically-dominated decoys might have value in sending a clear signal to businesses that such options are harmful to consumers and should not be used, but such a ban could potentially be circumvented by the use of a close decoy that is only marginally superior in one product attribute.

In the absence of a ban, the enforcers of consumer law must rely on the general legislative provisions that protect consumers from unfair trading in the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024. These could include the prohibition against misleading actions or misleading omissions, or a contravention of the requirements of professional diligence. However, enforcement on the basis of any of these might prove to be more difficult, as their applicability to these practices is less clear, or depends on several subjective ‘tests’ in relation to which it can be difficult to predict the view a court would take.

An additional way to act against the use of manipulative decoys may be through the use of outcomes-based regulation. In the UK, this is currently restricted to financial services, where the FCA can apply the Consumer Duty, and for any firms that become designated by the CMA as having strategic market status with regard to particular digital activities as part of the new pro-competitive digital competition regime. We would expect that the regulator would be able to enforce against the manipulative use of decoys by any firms falling within these regulations. The FCA explicitly states that firms must ensure that their choice architecture is not designed to influence consumers to select a particular option that benefits the firm but may not deliver a good outcome for the consumer. As part of the new digital competition regime, the CMA can apply bespoke codes of conduct to designated firms. These codes can include obligations on firms to provide clear, relevant, accurate, and accessible information, with which the use of decoy offers may not be compatible.

Ofcom, the sectoral regulator for telecoms, has not adopted an outcomes-based regulatory approach to ensuring consumers are fairly treated, but it has developed a set of voluntary ‘Fairness for Customer’ commitments to strengthen how companies treat their customers. Our evidence suggests that the use of decoys in the broadband market is in tension with these voluntary obligations. In particular there are two obligations that are difficult to reconcile with the use of decoy options. These are:

- Customers get a fair deal, which is right for their needs. Providers offer customers packages that fit their needs and have a fair approach to pricing. Prices are clear and easy to understand.

- Customers are supported to make well-informed decisions with clear information about their options before, during, and at the end of their contract. Providers design and send communications in a way that reflects an understanding of how customers generally react to information so that they can understand and engage with the market.

While the ‘Fairness for Customer’ commitments are voluntary, Ofcom has indicated it will have an ongoing assessment of whether customers are being treated fairly and that they are likely to be concerned where behavioural biases are exploited in ways that adversely affect consumers. We expect it to challenge firms that use decoy offers to demonstrate that their use does not break the commitments.

Annexes are available in the downloadable PDF.

Footnotes

[1] The additional expenditure per annum will depend on their preferred broadband package without a decoy present. The monthly costs used in the experiment are presented in Table 1.

[2] At the time of writing this is the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, but which will be repealed and replaced by the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 that is expected to come into force in 2025.

[3] A further advantage of the broadband market is that the product attributes are both easily comparable and quantifiable, in contrast to those in some other markets that are more difficult to quantify into an objective monetary benefit, such as gym subscriptions that include the ability to book classes 14 days in advance.

[4] A further type of decoy effect is a similarity effect in which the introduction of an option that is similar to the competitor option increases the perceived desirability of the target option.

[5] An alternative type of decoy, but which can also be used to create an attraction effect are phantom decoys. These are options that are shown to the customer despite being unavailable for purchase, perhaps because they have been discontinued or are sold out, and which make a target option more attractive.

[6] In discrete choice experiments, participants are presented with hypothetical scenarios where they must select their preferred choice from the options shown. The selections are analysed to uncover the participants’ underlying preferences.

[7] False hierarchy is when one option is made to stand out more e.g. through colour, size or placement on a page.